ARTICLE AD BOX

The adult-education program at Federal Correctional Institution Danbury needed a civics teacher. Conveniently, a new prisoner with a history of intimate involvement in American politics—inmate No. 05635-509—needed a work assignment. And that is how Steve Bannon, the man who stood accused of helping orchestrate an effort to undermine American democracy and to overturn a presidential election, found himself on the federal payroll making 25 cents an hour teaching civics to fellow convicts.

Bannon’s class met up to five days a week, with as many as 50 inmates showing up for the sessions. Whether that impressive attendance had more to do with Bannon’s lectures or the sweltering summer heat is anyone’s guess—the classes were held in one of the only buildings at Danbury with air-conditioning. In class, he taught the story of the American founding, referencing both The Federalist Papers and the writings of the anti-Federalists who believed that the Constitution gave the federal government too much power. His lesson plans described how the growth of what Bannon calls the administrative state betrayed America’s founding principles. After one class on the evils of the Federal Reserve and the national debt, Bannon says one of his convict students raised his hand to ask, “And they say we’re the criminals?”

The 70-year-old former chief strategist for Donald Trump had been found guilty on two counts of contempt of Congress. His crime: defying a subpoena and refusing to cooperate with the congressional committee investigating the January 6 attack on the Capitol. For four months, he would be housed in a two-story cellblock with 83 other men, all of whom shared two showers. Bannon’s willingness to serve time rather than cave to Nancy Pelosi cemented his status as a towering figure in the MAGA movement. “I am proud to go to prison” if that’s what it takes “to stand up to tyranny,” he’d told reporters on the day he showed up to serve his sentence.

Danbury is not the kind of prison where you would typically find someone like Bannon. But because he had another pending legal issue—he later pled guilty to one felony-fraud count in New York related to a fundraising campaign—he could not be sent to one of the minimum-security prisons, sometimes referred to as “Club Fed,” where inmates live relatively comfortably. Bannon wants you to know that he was locked up with hardened criminals in a real prison.

[From the July/August 2022 issue: American Rasputin]

Just a couple of weeks after his release, I sat down with Bannon in the cluttered living room of his townhouse on Capitol Hill. We spoke for nearly three hours about his time in prison. It was a dialogue that started with a phone call the day he was released, in late October 2024, and continued over dozens of telephone interviews as the former inmate resumed his role as one of Trump’s most important outside advisers. As we talked about Trump’s return to power, our conversations often came back to Bannon’s experience behind bars.

“I wasn’t in a camp like that pussy Cohen,” Bannon told me, referring to Trump’s former fixer Michael Cohen. Danbury is, in Bannon’s words, “a rough place”—“a fucking low-medium security with gangbangers and fucking drugs and stabbings.” Soon after he arrived, he told me he saw a group of inmates “take a shiv out and fucking rip a guy.” There was “blood everywhere.” When police officers asked Bannon what he’d seen, he refused to tell them anything. “You just can’t,” he said. “You answer any question a cop asks you, and you’re done.” He was eager, though, to tell me about the “murderers, fuckin’ mob hitmen, who were my besties.”

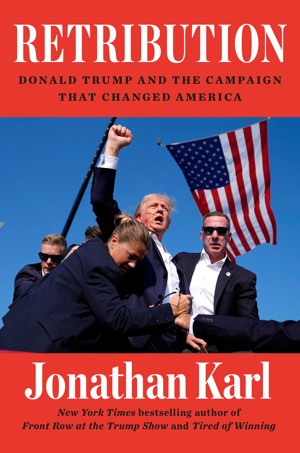

This article has been adapted from Jonathan Karl’s book, Retribution: Donald Trump and the Campaign That Changed America.

This article has been adapted from Jonathan Karl’s book, Retribution: Donald Trump and the Campaign That Changed America.

Among the prison’s few amenities is a small room with three TVs—“a Spanish TV, a white TV, and a Black TV”—behind a glass barrier; inmates can use handheld radios to listen to the TV of their choice. One evening in July, all three were tuned to the same channel, to the reports from a Trump rally in Butler, Pennsylvania.

Bannon had been in the computer room when a guy raced down to get him: “Hey, boss,” the inmate said. “Trump shot.”

“What?”

“Trump shot.”

Bannon had long feared that something like this would happen. I had spoken to him weeks before his prison sentence began, and he told me the only way Trump wouldn’t return to the White House was if the election was stolen or he was assassinated. “I’m very worried,” Bannon said. The Democrats, the media, “they’re giving moral justification that whoever takes [Trump] out is a hero.” In a speech that summer, he warned a crowd in Detroit, at a conference sponsored by Charlie Kirk’s Turning Point USA, that “between now and Election Day, they’re going to try to take out so many people.” It was, he predicted, “victory or death!”

Now, watching the news through the protective glass, he was convinced his fears were coming true. The Secret Service had failed to protect Trump. A gunman had taken a shot at him. Bannon watched as a blood-flecked Trump stood up and shouted, “Fight! Fight!” Had Bannon not been in prison, he would have immediately taken to the airwaves to amplify that message.

At the time, I had one thought: America is lucky that Steve Bannon is behind bars.

For as long as Bannon has been in Trump’s orbit, he has been the voice channeling the anti-establishment rage at the heart of the MAGA movement, preaching a no-compromise, screw-your-opponents, tear-down-the-institutions approach to politics. He used his post as “chief strategist” in the first Trump presidency to go after Republicans inside and outside the White House who were unwilling to do what was necessary for Trump to transform Washington. Bannon kept a list of Trump’s major campaign promises on a whiteboard in his West Wing office. After seven months, only a few items were checked off, and Bannon was fired. The truly radical Trump presidency would come later.

Bannon wasn’t out of Trump’s good graces for long, though. And unlike many of Trump’s allies, he did not waver in his support after the failed attempt to overturn the election. In fact, he became even more devoted, building his video podcast, War Room—the twice-daily dose of resentment and retribution for Trump supporters—into the center of the MAGA-media ecosystem. The show guided hard-core Trump supporters through all of the state election recounts in early 2021 and helped spread the bonkers theory that the former president could be reinstated before the next election. The plan to oust Kevin McCarthy from the speakership in 2023 had been largely hatched on Bannon’s show. Trump himself was a regular viewer. At least once, Bannon interrupted an interview to answer his phone. “Hey, Mr. President,” he said. “I’m live on TV; can I call you back?”

Bannon lined up an eclectic group of about 20 guest hosts—including his daughter Maureen, Rudy Giuliani’s son, and Osama Bin Laden’s niece—to keep the podcast going while he was behind bars. “I’m not a journalist. I’m not in the media,” Bannon said shortly before going to prison. “This is a military headquarters for a populist revolt. This is how we motivate people. This show is an activist show. If you watch this show, you’re a foot soldier. We call it the Army of the Awakened.”

But even while he was imprisoned, he found ways to wield his influence. One of the first things I talked with Bannon about after his release was the assassination attempt. If Trump had shown up to the convention declaring, “‘Fuck them, they tried to kill me,’ I think the country would have been on fire,” I told Bannon. “He calmed it down.”

“He calmed it down, yes,” Bannon replied.

“But you would have been fanning the flames.”

“Throwing fucking gasoline on it. Fuck yes!” Bannon shot back. “I would have revved that thing up to a 10.”

And, he added, cryptically: “I’m not saying I didn’t make that recommendation through code.”

Through code?

Yes, Bannon had a way of getting messages to the Trump campaign—and to Trump himself—while he was behind bars.

In prison, Bannon spent as much time as he could in the computer room, using one of the four PCs—equipped with a two-decade-old Windows operating system—that were shared by the 84 prisoners in his cellblock. He would sign up to use the computers for an hour, and then, after a 15-minute break, sign up again. Bannon was cognizant of “prison etiquette” about not hogging the computers, but said that he would sometimes spend 10 hours a day “working on campaign stuff.”

[David A. Graham: What to cheer about in the sentencing of Steve Bannon]

The devices were not connected to the internet, but he could communicate via email with a few dozen preapproved individuals. The Bureau of Prisons would review the correspondence on its way in and on its way out. His daughter Maureen, whom he calls Mo, and his chief financial officer, Grace Chong, helped him keep up with the news. “They had a system of sending me, first off, all polling data, everything like that, analytics,” he remembered. “They would send it to me, and I’d be able to comment and ask questions.” They also sent him images of various news websites so he could see what stories were online even though he didn’t have direct access to the internet. “I’d have 50 stories. I couldn’t click on the stories, but I said, ‘Send me boom, boom, boom.’ And they’d cut and paste and drop it in there.”

Bannon claims that an investigative officer at Danbury—an official he described as “pure MAGA”—had warned him that his communications were being reviewed by “Main Justice,” otherwise known as the Biden administration. So he developed a coded system to let “the girls” know which messages were to be passed on to Trump or to those around him, in particular the aide Boris Epshteyn: “I had just a system to get to Boris, kind of in quasi-code, through Mo into Grace,” he said. Was there literally a code word? “Well, we had—” he began, before catching himself. “I don’t—the Bureau of Prisons could go back through it. We had a way that they could get to him.”

And in the days following the assassination attempt, Bannon let campaign officials know that he believed they were making a huge mistake by trying to reduce tensions rather than raise them.

“Trump’s going to be Trump. You’re not going to have that ‘unity,’” he remembered saying. “What you’re going to do is blow a huge opportunity to differentiate yourself. And quite frankly, throw down harder that they tried to assassinate him. Put it back on them. Get into the thing about the lax security. Double down, triple down on this. It’s a winner.”

Fortunately, the campaign disregarded the advice. As Bannon watched speaker after speaker at the convention praise Trump’s message of unity, he found himself growing angrier and angrier. “I hated the convention,” Bannon told me. “The kumbaya, the cancellation of all the guys who wanted to get up there to fucking throw fucking fists.”

“If I had been around, that would have never happened,” he said. “Ever.”

Though much of Bannon’s attention for those four months was focused on the world outside Danbury, he said he learned a lot in prison.

“You can actually get a sense of where the country is in prison,” he told me. “Every Hispanic and Black family in America has someone they know that’s incarcerated; that’s just the reality. It may not be their son, but it’s a cousin, or nephew, or a next-door neighbor. These mass incarcerations are out of control for nonviolent drug charges.”

Bannon wanted me to know he didn’t hang out just with the other nonviolent offenders. One of his closest prison buddies was an Italian guy named Vito—”the single biggest Trump fan you’ve ever seen,” Bannon told me. “He could literally quote” Trump’s speeches.

Vito is a reputed member of the Columbo crime family named Vito Guzzo. He had been locked up for nearly three decades after pleading guilty to five murders and several other crimes, including arson, racketeering, and attempted murder. When he pleaded guilty in 1998, the judge asked him to describe his crimes. He did so with no emotion. “I killed Ralph Sciulla by shooting him in the head,” he said, reading from a piece of paper. “I killed Anthony Mesi by shooting him. I shot John Borrelli.”

Vito has been a free man since April. Bannon helped him get an early release—after serving 26 years of his 38-year sentence—through the First Step Act, the criminal-justice-reform bill signed into law by Trump in 2018.

A friend captured on video the moment Vito walked out of Danbury—swaggering in a white Sergio Tacchini tracksuit, pristine tennis shoes, and dark sunglasses, his hair slicked back.

“Come on,” Vito can be heard saying as he gives his girlfriend a hug. “Let’s get out of here.”

Vito’s girlfriend sent the video to Bannon, who watched with gleeful pride at his friend’s composure. “That guy is so impressive,” Bannon told me. “Look at that guy’s tracksuit; look at the shoes; look at the hair.” Nearly three decades behind bars and he “walks out, totally precise. These guys amaze me.”

Bannon had been a critic of the First Step Act—it was one of the only things he disagreed with Trump about. The initiative, which sought to improve conditions in prison and to give inmates more opportunities for education and early release, had been pushed by Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, whom Bannon often clashed with. Now Bannon had come around. “Jared was a genius about this. It is our ticket to a massive coalition,” Bannon told me. “Remember, in Spartacus the slave revolt starts in a prison, right?”

(Though Bannon expressed what seemed to be genuine concern for the treatment of the inmates he got to know at Danbury, his compassion for the accused was far from consistent. He had only praise for the Trump administration for flying two planeloads of alleged Venezuelan gang members, without the benefit of a hearing or reasonable notice, to the CECOT prison in El Salvador—a place that actually resembles hell on Earth. “Guess what, if there are some innocent gardeners in there? Hey, tough break for a swell guy,” Bannon said on War Room in March.)

[Read: No one was supposed to leave alive]

Bannon’s time in Danbury convinced him that Trump was going to win again. In his view, he told me in October, Kamala Harris was doomed by her record as a prosecutor in California. “No Black or Hispanic men are going to vote for Kamala Harris, because of the mass incarcerations,” he told me. “The Black community, the Hispanic community, they literally hate her.” Prison, he said, “is the most MAGA place I’ve ever been in my life, from the minorities.” (According to a Navigator Research postelection survey, Harris won 49 percent of the Hispanic-male vote and 71 percent of the Black-male vote. Directionally, though, Bannon’s broader point stands: Joe Biden did 35 percentage points better than Harris among both groups in 2020.)

But the main thing Bannon learned in prison is that he doesn’t want to go back there. He was released on October 29, at 3 a.m.—because prison authorities wanted to avoid the commotion of a press conference. As he walked out of the prison gate, he was met by Maureen, who ran over and gave him a hug. It was exactly one week before the 2024 election, and within hours of his release—before 6 a.m.—Bannon’s phone lit up. Donald Trump was on the line.

“My Steeeeeeve! My Steeeeeve!” Trump said as they both laughed. “You’re a convict.” The former president had lots of questions for Bannon about his life behind bars. If Trump lost the election the following week, there was a very real chance that he would end up in prison. How bad was it?

“Let me be blunt,” Bannon told Trump. “It’s hard as shit. So we’re not going there.”

Trump didn’t go to prison, obviously; he went back to the White House. And his second term is proving to be far more consequential, more radical, and more lasting than his first.

He has put his personal legal team in charge of the Justice Department, squeezed top law firms to do his bidding, and upended a half century’s worth of ethics and anti-corruption reforms by mixing family business deals with government business. He is attempting to use the Federal Communications Commission to police and punish television networks that he says treat him unfairly and is pressuring U.S. attorney’s offices to prosecute his political enemies.

Trump hasn’t always taken Bannon’s advice on policy, but Trump’s brazen attack on norms and on his real and perceived enemies is exactly what Bannon has been preaching. From his powerful post on War Room, Bannon is pushing the aggrieved president to use his power to not just defeat his enemies but destroy them, and Trump is pursuing that agenda to a much greater degree than he did the first time around.

The unity talk Bannon so despises is gone completely. Two days after the killing of Charlie Kirk, Bannon attacked Republicans who were calling for people to turn down the partisan rhetoric. Bannon hated it when Governor Spencer Cox stepped forward the day Kirk was killed and said we had to “stop hating our fellow Americans.”

“We’re not gonna say it’s a time to bring people together,” Bannon told the foot soldiers of the MAGA movement. “You know why? One side has to win here.”

At times, Trump still turns to Bannon for guidance, as if he were working down the hall from the Oval Office. Case in point: Bannon’s previously unreported role in the events leading up to President Trump’s remarkable confrontation with Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House in February.

On Monday of that week, President Trump convened his top national security advisers in his dining room adjacent to the Oval Office. It was a busy time. French President Emmanuel Macron had just met with Trump, and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer was due soon. Both were pleading with Trump to continue military support for Ukraine and its president. Zelensky himself would be coming to Washington in a few days, though the visit had not yet been announced.

Trump’s advisers had worked out an agreement with their Ukrainian counterparts whereby, in exchange for continued military support, Ukraine would promise the United States a share in the development of its natural resources, including its deposits of rare-earth minerals. But as Trump reviewed the draft agreement, he didn’t like what he saw, believing the terms were not favorable enough to the United States. He looked out at the most important officials in his administration: Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Special Envoy Steve Witkoff, National Security Adviser Mike Waltz, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, and Vice President J. D. Vance. Then he turned to Waltz:

“Get Steve Bannon on the phone.”

Bannon saw Waltz calling and sent him to voicemail with a text: “The show is live. I’ll call you at noon.” A few minutes later, his phone rang again. This time he could see it was Trump calling from his personal cellphone. Bannon quickly went to commercial break, telling his producer to make it a long one.

“Yes, Mr. President.”

“Hey, Steve, I’ve got the boys here,” Trump said. “I’m going to put you on speaker.”

For the next 30 minutes, Trump had Bannon tell his national-security team, through the little iPhone speaker, why he didn’t like the deal and why he didn’t trust the Ukrainian leader.

“I hear you don’t love this deal,” Trump said.

“I fucking hate it,” Bannon said. “I hate everything to do with it.” He said he understood that Trump wanted to recoup the $350 billion that he estimated the U.S. had spent on Ukraine. But the deal “ties us to Ukraine.” Bannon, who knew there had been talk of a Zelensky meeting, referred to the Ukrainian president as “that punk”: “If that punk comes here, he’s going to want a security guarantee,” Bannon said. “You can’t trust him. You can’t trust any of the Europeans. You can’t trust Putin either, but these guys are really slippery.”

[Read: A man who actually stands up to Trump]

The rest of the saga surrounding Zelensky’s visit to Washington is an extraordinary piece of U.S. history, and there’s little doubt that Bannon’s advice set the tone for the coming conflict.

“You’re not in a good position,” Trump told Zelensky, his voice rising. “You don’t have the cards right now.”

“I’m not playing cards,” Zelensky interrupted.

“You’re playing cards,” Trump shot back. “You’re gambling with the lives of millions of people. You’re gambling with World War III.”

“What are you speaking about?” Zelensky asked.

“You’re gambling with World War III,” Trump repeated. “And what you’re doing is very disrespectful to the country, this country that’s backed you far more than a lot of people said they should have.”

It was the kind of tough-guy language that would make a mob hitman proud.

For nearly a century, America had helped keep peace in Europe, standing shoulder to shoulder with our allies against aggressors. But there in the Oval Office, Trump was doing more than berating an American ally; he was declaring to the world that America was no longer the country that, in John F. Kennedy’s words, would “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.” Now a U.S. president was showing an ally the true meaning of “America First.”

Trump’s final words before the cameras left the Oval Office made clear that, although Trump was angry, he was also enjoying himself. “All right, I think we’ve seen enough,” Trump said to the shocked reporters in the room. “What do you think? This is going to be great television. I will say that.”

Great television, perhaps, but, thanks in part to Trump’s favorite convict, Trump is now doing far more than playing to the television cameras. He’s changing America in ways that will long outlive his presidency.

This article has been adapted from Jonathan Karl’s book, Retribution: Donald Trump and the Campaign That Changed America.

.png)

8 hours ago

2

8 hours ago

2

English (US)

English (US)